The Becoming Radical: 2014 NCUEA Fall Conference: Thirty Years of Accountability Deserves an F

Thirty Years of Accountability Deserves an F:

Education Accountability as Disaster Bureaucracy

[Access the supporting “Social Context Reform: Moving from Accountability to Equity in Education” in PowerPoint here.]

The accountability puzzle isn’t hard to put together because the pieces are in clear sight and fit together easily, but political, media, and public interest in facing the final picture is at least weak, if not completely absent.

Part of the problem is that the picture spans a tremendous amount of time for public consciousness.

The standards movement reaches back to the 1890s with The Committee of Ten.

Influential English educator and former NCTE president Lou LaBrant lamented in 1947 “…the considerable gap between the research currently available and the utilization of that research in school programs and methods” (p. 87).

And as a result, LaBrant urged: “This is not the time for the teacher of any language to follow the line of least resistance, to teach without the fullest possible knowledge of the implications of his medium” (p. 94).

So let’s move forward to the foundation of the current thirty-plus-year accountability movement: A Nation at Risk.

Gerald Bracey (2003) and more directly Gerald Holton (2003) exposed that the stated original intent under the Ronald Reagan administration was to create enough negative perceptions of public education through A Nation at Risk to leverage Reagan’s political goals:

We met with President Reagan at the White House, who at first was jovial, charming, and full of funny stories, but then turned serious when he gave us our marching orders. He told us that our report should focus on five fundamental points that would bring excellence to education: Bring God back into the classroom. Encourage tuition tax credits for families using private schools. Support vouchers. Leave the primary responsibility for education to parents. And please abolish that abomination, the Department of Education. (Holton, n.p., electronic)

The accountability formula spawned after A Nation at Risk swept the popular media included standards, high-stakes testing, and increased reports of public school failure.

While the federal report created fertile ground for state-based school accountability, that proved not to be enough for political leaders, who within 15-20 years began orchestrating national versions of education accountability. The result was No Child Left Behind and then Common Core standards and the connected high-stakes tests—both neatly wrapped in bi-partisan veneer.

About thirty years after Reagan gave the commission that created A Nation at Risk the clear message about the need for the public to see public education as a failure, David Coleman, a lead architect of Common Core, exposed in 2011 what really matters about the national standards movement; after joking about having no qualifications for writing national education standards, Coleman explained:

[T]hese standards are worthy of nothing if the assessments built on them are not worthy of teaching to, period. This is quite a demanding charge, I might add to you, because it has within it the kind of statement – you know, “Oh, the standards were just fine, but the real work begins now in defining the assessment,” which if you were involved in the standards is a slightly exhausting statement to make.

But let’s be rather clear: we’re at the start of something here, and its promise – our top priorities in our organization, and I’ll tell you a little bit more about our organization, is to do our darnedest to ensure that the assessment is worthy of your time, is worthy of imitation….

There is no amount of hand-waving, there’s no amount of saying, “They teach to the standards, not the test; we don’t do that here.” Whatever. The truth is – and if I misrepresent you, you are welcome to take the mic back. But the truth is teachers do. Tests exert an enormous effect on instructional practice, direct and indirect, and it’s hence our obligation to make tests that are worthy of that kind of attention.

The pieces to the puzzle so far then: Education accountability began as a political move to discredit public schools, and next the Common Core standards movement embraced that above everything, tests matter most.

And now we have the final piece; Gerwertz reports:

In a move likely to cause political and academic stress in many states, a consortium that is designing assessments for the Common Core State Standards released data Monday projecting that more than half of students will fall short of the marks that connote grade-level skills on its tests of English/language arts and mathematics.

“Political and academic stress”—here we need to have context.

On Black Friday 2014—when the U.S. officially begins the Christmas holiday season, revealing that we mostly worship consumerism (all else is mere decoration)—we are poised to be distracted once again from those things that really matter. Shopping feeding frenzies will allow Ferguson, Tamir Rice, and Eric Garner to fade away for the privileged—while those most directly impacted by racism and classism, poverty and austerity remain trapped in those realities.

History is proof that these failures have lingered, and that they fade. Listen to James Baldwin. Listen to Martin Luther King Jr.

But in the narrower education reform debate, we have also allowed ourselves to be distracted, mostly by the Common Core debate itself. As I have stated more times that I care to note, that Common Core advocates have sustained the debate is both a waste of our precious time and proof that Common Core has won.

As well, we are misguided whenever we argue that Common Core uniquely is the problem—instead of recognizing that Common Core is but a current form of a continual failure in education, accountability built on standards and high-stakes testing.

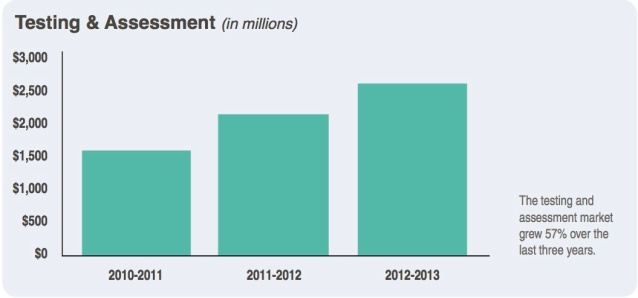

With the release of Behind the Data: Testing and Assessment—A PreK-12 U.S. Education Technology Market Report*, we have yet another opportunity to confront that Common Core is the problem, not the solution, because it is the source of a powerful drain on public resources in education that are not now invested in conditions related to racial and class inequity in our public schools.

Richards and Stebbins (2014) explain:

The PreK-12 testing and assessment market segment has experienced remarkable growth over the last several years. This growth has occurred in difficult economic times during an overall PreK-12 budget and spending decline….

Participants almost universally identified four key factors affecting the recent growth of the digital testing and assessment market segment:

1) The Common Core State Standards are Changing Curricula

2) The Rollout of Common Core Assessments are Galvanizing Activity….

(Executive Summary, pp. 1, 2)

(Richards & Stebbins 2014)

So Common Core advocacy is market-driven, benefiting those invested in its implementation. But we must also acknowledge that that market success is at the expense of the very students who most need our public schools.

And there is the problem—not the end of cursive, not how we teach math, not whether the standards are age-appropriate.

Common Core is a continuation of failing social justice, draining public resources from needed actions that confront directly the inexcusable inequities of our schools, inequities often reflecting the tragic inequities of our society:

As the absence or presence of rigorous or national standards says nothing about equity, educational quality, or the provision of adequate educational services, there is no reason to expect CCSS or any other standards initiative to be an effective educational reform by itself. (Mathis, 2012, 2 of 5)

Like Naomi Klein’s disaster capitalism—the consequences of which are being exposed in New Orleans, notably through replacing the public schools with charter schools—the Common Core movement is not about improving public education, but a form of disaster bureaucracy, the use of education policy to insure the perception of educational failure among the public so that political gain can continue to be built on that manufactured crisis.

Yes, disaster bureaucracy is an ugly picture, but it is evident now the accountability movement is exactly that.

Common Core is not some unique and flawed thing, however, but the logical extension of the Reagan imperative to use education accountability to erode public support for public schools so that unpopular political agendas (school choice, for example) become more viable.

The remaining moral imperative facing us is to turn away from political claims of school and teacher failure, away from their repeatedly ineffective and destructive reforms, and toward the actual sources of what schools, teachers, and students struggle under as we continue to reform universal public education: social and educational inequities that have created two Americas and two school systems that have little to do with merit.

Accountability built on standards and high-stakes testing (not Common Core uniquely) is the problem because it is a designed as disaster bureaucracy, not as education reform.

Who will be held accountable for the cost of feeding the education market while starving our marginalized children’s hope?

Let me end with two quotes from James Baldwin:

Reference

Bracey, G. W. (2003). April foolishness: The 20th anniversary of A Nation at Risk. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(8), 616-621.

Holton, G. (2003, April 25). An insider’s view of “A nation at risk” and why it still matters. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 49(33), B13-15. Retrieved March 26, 2010, from OmniFile Full Text Mega database.

LaBrant, L. (1947, January). Research in language. Elementary English, 24(1), 86-94.

Richards, J., & Stebbins, L. (2014). Behind the Data: Testing and Assessment—A PreK-12 U.S. Education Technology Market Report. Washington, D.C.: Software & Information Industry Association.

* Thanks to Schools Matter for posting, and thus, drawing my attention to the study.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.