Cloaking Inequity: Thoughts from a Former KIPP Teacher: Testing, Common Core, and Charters are Myths

In the bid for a better education for all students in America, recent reform efforts have focused on increasing the expectations – standards and exams – for students. What is not explicitly discussed are the negative ways that these standards and exams target students of low socio-economic status and minorities – we are enamored as a nation with the mantra that higher expectations equals greater success. Many argue that the major reason students of color and of low-income have not excelled is because of a basic lack of belief in educators and persistent racism and prejudice in the schooling system. But this is just one factor of many. Raising expectations without identifying and ameliorating the larger causes of lower performance among students of color and low socioeconomic status fails to engage with the deeper inequality that exists in this nation. However, focusing on standards as one of many means to bolster achievement in high poverty/high minority schools is a way to strive for equity. Unfortunately, as Diane Ravitch has accurately pointed out, the implementation of the standardization movement over the last 20 years has fallen short. The reasons for this are twofold. Increased standardization – like scripted curriculum – and testing are bound to decrease engagement, among the engaged, and especially the disengaged. Secondly, when tied to testing, even great standards fall short due to the pressure placed on teachers and students to perform. Systemic change and standardization, so far, have failed to alter the nature of academic success in this country, particularly for the students who typically “underperform.”

Walk into any major charter school today, and even a large number of public schools, and you are bound to see a sign that proclaims “high expectations” for all students. It may be a “no excuses” sign, a “never give up” sign, a chart of goals, school test scores, and so on. There is nothing wrong, inherently, with raising the expectations for all students. Cohen (1996) accurately describes the belief that “systemic reform would reduce inequality in educational achievement if disadvantaged students were held to the same high standards as everybody else and if schools could be made to improve education across the board” (pp. 101). The problem lies in both what those expectations are and how much weight is placed on raising the bar.

With NCLB and the current state of education, the expectations trickle down from high stakes exams. This is not enough. Not only do these exams maintain the competitive edge white middle and upper-class students have, but they reduce the quality of education students could conceivably receive with high expectations of success and rigor, great standards and great teachers. I have seen the effects of this first hand working in KIPP schools, where students have learned quite well how to perform on exams, but have developed few of the critical thinking and problem solving skills and habits so desperately needed today. Ravitch (2011) justifiably decries,

What was once an effort to improve the quality of education turned into an accounting strategy: Measure, then punish or reward. No education experience was needed to administer such a program. Anyone who loved data could do it. The strategy produced fear and obedience among educators; it often generated higher test scores. But it had nothing to do with education” (pp. 16).

This is the model in many charter schools today. You can coach and train a teacher to effectively “plan backwards” from an exam. They measure test questions (objectives) each day through exit tickets, effectively insuring that almost all students are prepared enough by the end of the year to be successful on the exam. You need to be able to break down a test, teach minute skills or facts within a lesson – these may or may not be interconnected by the teacher lesson-to-lesson or unit-to-unit – interpret data for weak spots, reteach, and assess again. Is this the equitable education that low-income students and students of color deserve?

Testing – What students learn from getting it right

Generally, there seems to be a grave fear of leaving high expectations alone, i.e. good standards, without all the tests to measure and compare. Tests, as opposed to authentic assessments, by their very nature reduce the complexity and rigor of the standards, prize the correct answer and “quick thinking,” and diagnose learning and success through single measures. They encourage both the teacher and the student to value beating the system instead of developing the person. Teachers present, and students find, no reason to work through tough problems, as it will do them no good on the assessment at the end of the year. This is the opposite of what most reformers proclaim to want out of these high expectations, new standards, and increased testing. They frequently express a strong desire transform schools so that “exploration and production of knowledge, rigor in thinking and sustained intellectual effort” (Smith and O’Day, 1990, pp. 246), complex thinking and problem solving, and real world engaging curriculum are the norm. Instead the results of reform efforts like NCLB have driven change that focused primarily on ”improving test scores in reading and math…produc[ing] mountains of data, not educated citizens” and promoting “a cramped, mechanistic, profoundly anti-intellectual definition of education. In the age of NCLB, knowledge is irrelevant” (Ravitch, 2011, pp. 8)

Conclusion – The Common Core, Has Anything Changed?

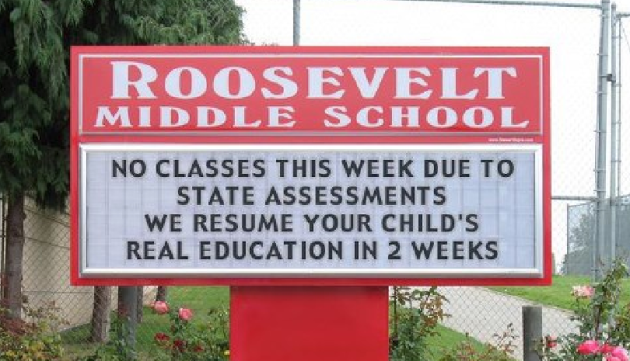

The Common Core Standards were once a beacon of hope. Schools across the nation would have one, rigorous measure by which to challenge and compare students. This new curriculum would engender a new sense of accomplishment in students, shaping them to be world competitors, and career and college ready. So, what happened? In my view, the CC have potential. The standards are not perfect. (See Common Core: Same Exclusion, Different Century). However, they are a more complex set of standards that could, given the right environment, empower teachers to develop engaging, rigorous curriculum, and promote true learning and development in their students. What’s the hitch? Testing. Most states have, or will, invest in heavy amounts of high stakes testing to “measure” the success of students. Already, in New York, students have reported hating school, crying during exams, feigning illness, and high levels of stress. School is not a place they want to be. Parents of all stripes are beginning to protest. The question is, can this country, or the states, figure out how to raise the bar effectively without a giveaway to testing companies? Can we invest in the resources to train teachers and then trust them to educate our kids will, using a set of agreed upon expectations? The answer to this remains elusive…

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.