Letters from the Future (of Learning): In Atlanta, A School That Embodies Innovation

The first time I visited Mount Vernon, a PreK-12 private school on the outskirts of Atlanta, it was seven years ago – and I was underwhelmed.

The last time was a month ago, and I was blown away.

Let me explain.

Back in 2016, when I arrived as part of a team (led by my partner, Trung Le) tasked with designing Mount Vernon’s new high school, I’d been told to expect cutting-edge innovation. Yet as I shadowed a 10th-grader through her day, I felt like I could have been in any school, anywhere, at any time over the past century: with kids in traditional school uniforms, AP courses and Geometry exams, and 45-minute subject-specific periods, marked by a passing bell.

There was lots of good instruction, and the place was joyful and vibrant – but innovative? No.

I asked the school’s Head of School, Brett Jacobsen, to tell me what I was missing.

He told me the story of Dayton’s Department Stores.

Across the middle years of the 20th century, Dayton’s had steadily become a profitable player in the retail world. By 1960, that world – and the sort of consumer behavior that fueled it – showed no signs of letting up.

Yet the leadership saw an arc at the edges of the retail landscape, one that augured big changes ahead. And so in what was seen as a risky move at the time, Dayton’s announced its plan to open a very different sort of store, separate from its main business – a place that combined the best and most familiar aspects of the traditional department store experience with unprecedented low prices.

They decided to name it Target.

I don’t need to tell you the rest of the story.

When I asked Brett to explain the relevance of this story to Mount Vernon, he told me about a part of the school that wasn’t part of my assigned student’s schedule: the Innovation Diploma – a small, nascent, opt-in learning track at the high school in which all work was inquiry-driven, competency-based, and socially embedded. Then he took me to the Lower School, where the typical school-day had already been restructured in ways that were likely to create more students who would want the sort of experience the Innovation Diploma was offering.

These innovations, he explained, were his Target. “Schools today might as well be a chain of Department Stores. They’ve been successful for a long time, and despite the many changes on the horizon, a lot of them are likely to remain successful doing what they’ve always done for the short- and maybe even the medium-term.

“But there’s an arc at the edge of our landscape as well – the reordering of our relationship to knowledge. So just as Dayton’s seeded Target with the hope that, if it worked, it would put the parent organization out of business, we need to launch a thousand Trojan Horses of our own – future seeds of creative destruction that can attack all our most intractable rituals and assumptions, in order to usher in a different way of being that is more in line with both the modern world and the modern brain.”

I share that story because earlier this year I returned to Mount Vernon for the first time since 2016 – both to see the results of the high school we designed for them, and to get a sense of how far their Trojan Horse experiments had spread.

This time, everywhere I looked, I saw the seeds of what had first been planted all those years earlier.

Each floor in the 60,000 square-foot space is called a District, and is organized via two Neighborhoods and a Bridge that connects them – with a STEM lab on one side, and a Maker Space on the other. No teacher is assigned to a classroom, and all interior walls are moveable (and soundproof).

“Our teachers are forced to confront physical spaces here,” Jacobsen explained, “and to think about them, and to open the possibilities those different spaces provide. This bakes in a constant lever for change. Our greatest compliment is when people say that this place does not look like a school.”

The reason is not merely an aesthetic one. “Our strategy as an institution is to respond to the disruptive forces in the world right now. More than anything, we’re trying to fully live out what it means to support students of inquiry, innovation and impact.”

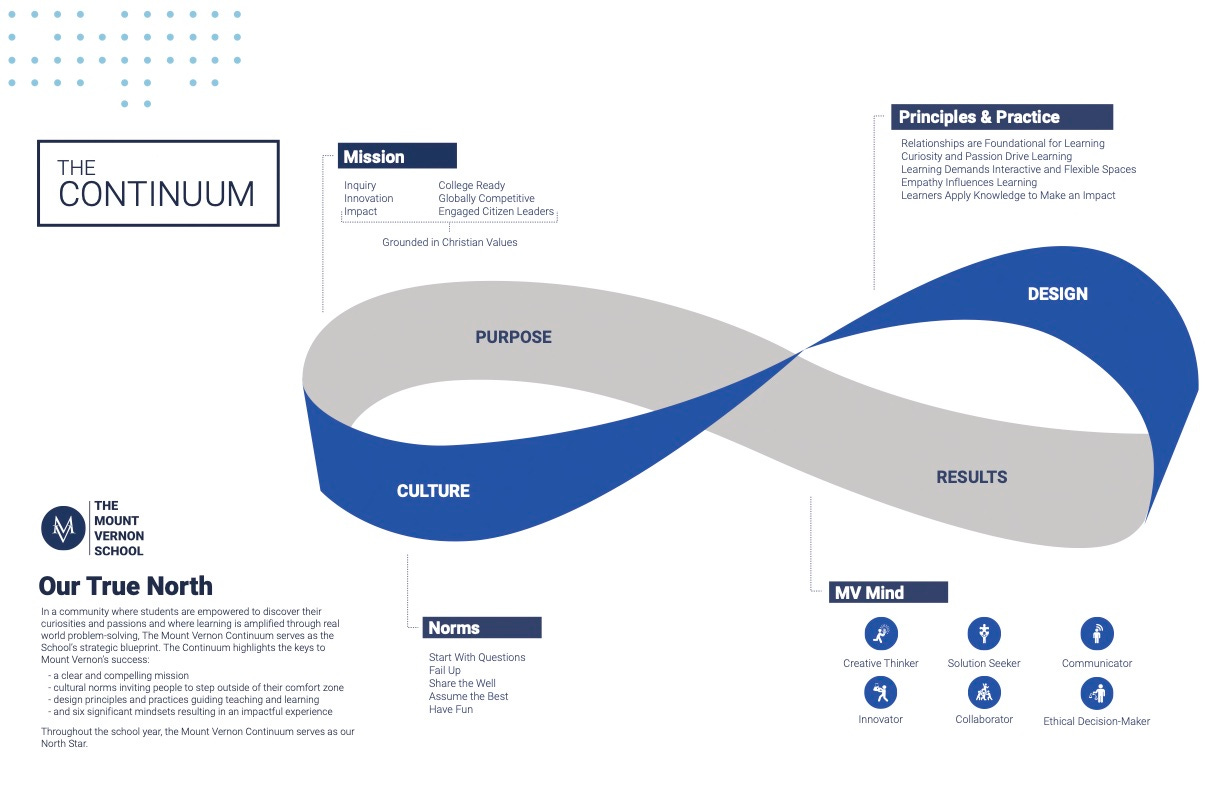

To that end, Mount Vernon has achieved a mobius-strip-shaped level of clarity (literally) about who they are, what they value, and what sorts of citizens they hope to graduate. They operate on nine-week learning modules and a five-period day – one of which is called GTD (for “Get Things Done”). Students take four courses at a time, some of which are grade-specific, while others are open to kids of all ages.

Because the courses are shorter, there is a richness to their variety – everything from The Art of DJ to Interactive Game Design to That’s Unconstitutional . . . Or Is It? But the crown jewel of the school is the Innovation Diploma (ID), which is no longer a small boutique-y experiment, but a distinct learning pathway in the school that involves around 30% of the student body – all of whom must apply to be accepted.

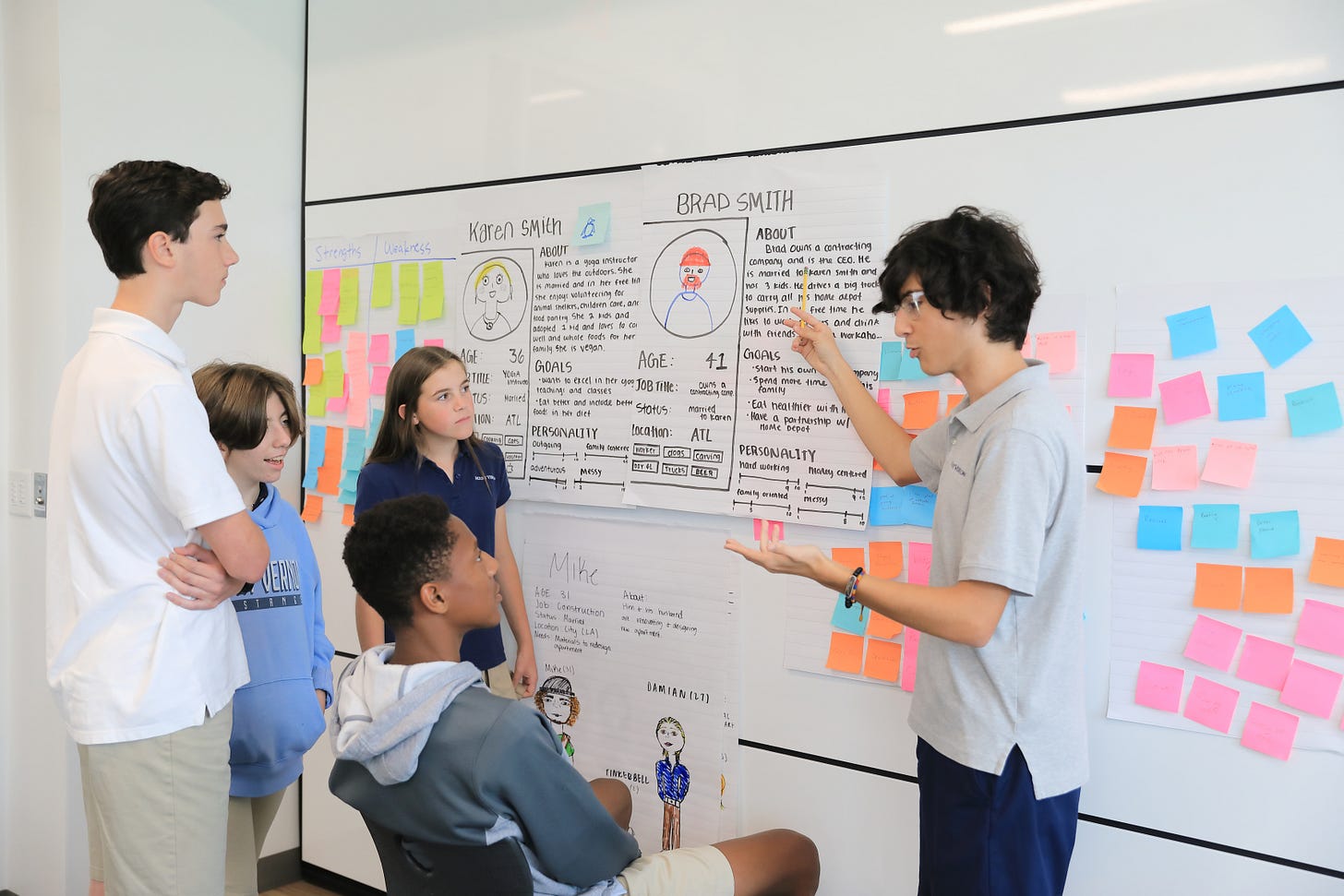

“ID is our test kitchen,” explained teacher Emily Wilcox. “We want to come up with new ideas here that can spread. It can be uncomfortable because you have to step back and really let the students lead – all the time. Initially, the curriculum for the ID is very inward facing – a foundational set of courses that help build a toolbelt for the work to come. Once that belt is formed, the second half of the experience is all outward facing – real projects for real clients, with real deliverables ranging from graphic design to live event production.”

The day I visited, I watched as a group of ID students were working with a local charity to help redesign their digital presence – from their website to their social media accounts. “Now,” Wilcox continued, “our kids have better stories to tell when they apply to college. They even have their own podcast – Getting into Good Trouble – and they are constantly helping us reimagine the way we live and learn together.”

I asked Jacobsen to reflect on what it took to reach this point. “Initially,” he said, “the window of our brand was far out ahead of our actual capacity. We said we were going to embody innovation and Design Thinking long before we actually did any of those things well. And we hadn’t yet developed any shared language around who we aspired to be, and what we most wanted to see embodied in our students.

“But you can’t be afraid to start claiming that space even before you get there.

You can’t connect the dots forward, only backward. But you must trust that the dots will connect.”

(If you like what you see, by the way, and/or if your community has a design need of your own, give us a shout . . .)

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.