The Becoming Radical: To Catch a Cheat: More on the Pearson Problem as Our Problem

“Cheating by test takers is becoming more common in the United States and throughout the world,” explains T.J. Bliss, adding:

In the past year, multiple news agencies have reported several instances of cheating on high-stakes tests. Recently, news broke that doctors in a variety of specialties had cheated to pass certification exams (Zamost, Griffen, & Ansari, 2012). In another instance, high school students were arrested and charged with misdemeanors and felonies for cheating on the SAT (Anderson, 2011). At a university in Florida, over 200 students admitted to cheating on a midterm exam when faced with accusations based on statistical evidence (Good, 2010).

So what are teachers to do? Bliss offers evidence-based solutions:

There are many ways to detect cheating, some more useful and reliable than others (Cizek, 1999). Proctors and invigilators can walk the exam room and directly observe some forms of cheating, like answer copying. This method will not work, though, if a person cheats by gaining pre-knowledge of exam items (Good, 2010), is taking the exam for someone else (Anderson, 2011), or is trying to memorize items to share with others (Zamost et al. 2012). Some cheating is detected through whistle-blowers, manual comparison of answer and seating charts, and other qualitative approaches (Cizek, 2006). However, in both large-scale and classroom testing situations, statistical approaches have also been used to identify suspected cheaters. Such methods have been successfully utilized to detect several different kinds of cheating, including answer copying, collusion, pre-knowledge, and attempts to memorize items.

And why the increased cheating? It seems legislation, competition, and technology have roles in that:

With the passage of legislation requiring increased school accountability (e.g. No Child Left Behind Act, 2001) and increased compet[ti]iveness for jobs requiring certification (United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010-2011) the stakes for passing standardized and licensure exams have increased dramatically. At the same time, technologies to enable cheating have also increased. For instance, some examinees have begun using smart phones, digital recorders, and other personal electronic devices to cheat during exams. Fortunately, the advent of new methods for administering exams (like Computer Adaptive Testing) and analyzing test results (like Item Response Theory) have led to the development of more complex and sensitive statistical methods to detect cheating.

For classroom teachers seeking ways to prevent cheating and catch students who cheat, the Internet offers a nearly endless supply of strategies:

- Prevent Cheating on Exams

- Student Assessment / Cheating

- Prevention and Detection of Cheating on Exams

- Essential Ways to Prevent Cheating in Online Assessments

To be honest, I could continue that list for dozens and dozens of bullets, all of which have about the same strategies.

How many of us as classroom teachers at all grade levels have given traditional tests such as multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, matching, etc., formats? How many of us have implemented some or many of the cheating prevention strategies commonly taught in methods courses such as creating several versions of the tests, asking students to cover their work, re-arranging desks and seating assignments, walking around the room during the tests?

And how many of us are outraged at Pearson and other testing corporations for monitoring social media in order to detect cheating and thus to protect the credibility of their product (as any business would do in a consumer society)?

How many of us as classroom teachers are rightfully angry about the misuse of value-added methods (VAM) for teacher evaluation and pay, and then hold our students accountable for tests in traditional formats in our classes?

How many of us help select, purchase, and then implement commercial programs for teaching and assessing our students?

*

I teach and co-teach several methods courses for candidates seeking certification to teach in high school. As a critical educator, my classes go something like this: For Topic A, here is what traditional/progressive educators say you should do, but here is what critical educators suggest.

Yes, this is a bit tedious, for me and, I suppose, my students.

In the methods course I co-teach, I am responsible for assessment, so the topics of tests and cheating are addressed.

In order to help my future teachers develop a critical lens, we often talk about their experiences with assessment and cheating while college students—by focusing on writing essays and being monitored for plagiarism.

Most of these students are familiar with directly or indirectly faculty using TurnItIn.com to evaluate plagiarism in student essays. And like most of the faculty, my students see nothing problematic about using that technology both to discourage and detect cheating.

As high-achieving students, my students tend to be harsh about cheating—until we start investigating their own behavior as students. Until we start unpacking what counts as cheating (for example, TUrnItIn.com allows each professor to manipulate the threshold for plagiarism, thus changing what counts as plagiarism from course to course).

Is sharing homework cheating? Is collaborating while writing an essay cheating? Is peer-editing an essay cheating?

And then we go further by asking why students cheat, and considering why students plagiarize.

Certainly all college students know not to plagiarize.

My larger point is about the conditions created in the classroom that foster cheating.

I explain to my students why I don’t give grades and don’t use traditional tests. My students submit multiple drafts of all essays and often spend a good deal of time in class drafting with me there to help.

I also detail how I incorporate a group midterm exam in my foundations of education course, the testing format being both small-group and whole class discussion with a focus on learning being a social construct.

I have consciously over 30-plus years sought ways to end the sort of testing culture that fosters cheating and instead implemented approaches to assessment that encourage full engagement that makes cheating (typically) not even an option.

Unable to avoid my English teacher Self, I tend to add that in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a powerful theme addresses the consequences of “reduced circumstances”; the main character Offred/June, who appears to be a decent person before the world crumbles, expresses murderous cravings—fantasizing about stabbing someone with a knitting needle and feeling the blood run warm over her hand.

This dystopian novel forces readers to consider the sources of the violent urges—are they inherent in Offred/June or prompted by her reduced circumstances?

That same sort of critical inspection must be a part of both the wider education reform movement and our own classrooms.

Under high-stakes accountability, why the cheating scandals in Atlanta, DC, and elsewhere?

But also, why are students cheating in our classes?

Why do students not read assigned works? Why do students claim they hate to read?

As teachers and public school advocates, to maintain our gaze only on outcomes is to miss the reasons for those outcomes, and to avoid our own culpability.

*

And then we come back to Pearson and the commercial boom connected directly to the accountability era.

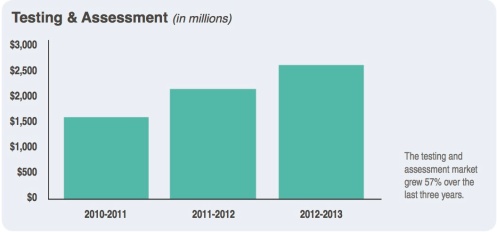

A Software & Information Industry Association report reveals, “testing and assessment products–which include software, digital content and related digital services–now make up the largest single category of educational technology sales,” increasing by 57% since 2012-2013:

That tax-payer’s cash grab combined with what Anthony Cody calls “necessary surveillance” for national high-stakes testing is a cancer on the educational body—one that must be not only cured, but also eradicated and then prevented.

However, we must also admit that this cancer is the result of cancer-causing behavior.

As teachers and public education advocates, we must continue to fight the profits and surveillance of Pearson and other commercial interests, but we also must face our own bad habits.

While we raise our voices against misguided and harmful policy (including taking a professional and political stance), we should practice what we preach by creating classrooms that reflect our obligations and commitments.

So I completely agree when Peter Greene makes this pointed and accurate claim connected to Pearson: “You know what kind of test need this sort of extreme security? A crappy one.”

I also support Jersey Jazzman concluding:

But even more than that: a good teacher gives assessments that are largely cheat-proof. So if the PARCC people really think their exam can be gamed by students over social media, they are admitting they have created an inferior product. …

Further: if the assessment is any good, and is really measuring higher-order thinking, it likely can’t be gamed. It’s easy to cheat on a multiple choice exam; it’s much harder to cheat on a chemistry lab. And it’s nearly impossible to cheat on a choir concert, or a personal response to a novel, or number line manipulative. …

But if the PARCC is so vulnerable that a tweet by a student after the test compromises the entire exam, it must be useless — particularly as a measure of student learning.

However, I feel obligated to raise a concurrent point related to the opening of this post: If our own assessment practices need the amount of surveillance and diligence detailed for preventing cheating and catching cheaters, there is ample evidence some pretty suspect testing is happening in our classrooms as well.

Let’s end the tyranny of high-stakes standardized testing that has spawned Pearson et al., but let’s make sure we address that tyranny in our own practice as well.

For Further Reading

Email to My Students: “the luxury of being thankful”

Grades Fail Student Engagement with Learning

“Students Today…”: On Writing, Plagiarism, and Teaching

De-Testing and De-Grading Schools: Authentic Alternatives to Accountability and Standardization, Bower, Joe / Thomas, P.L. (eds.)

The Fatal Flaw of Teacher Education: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.