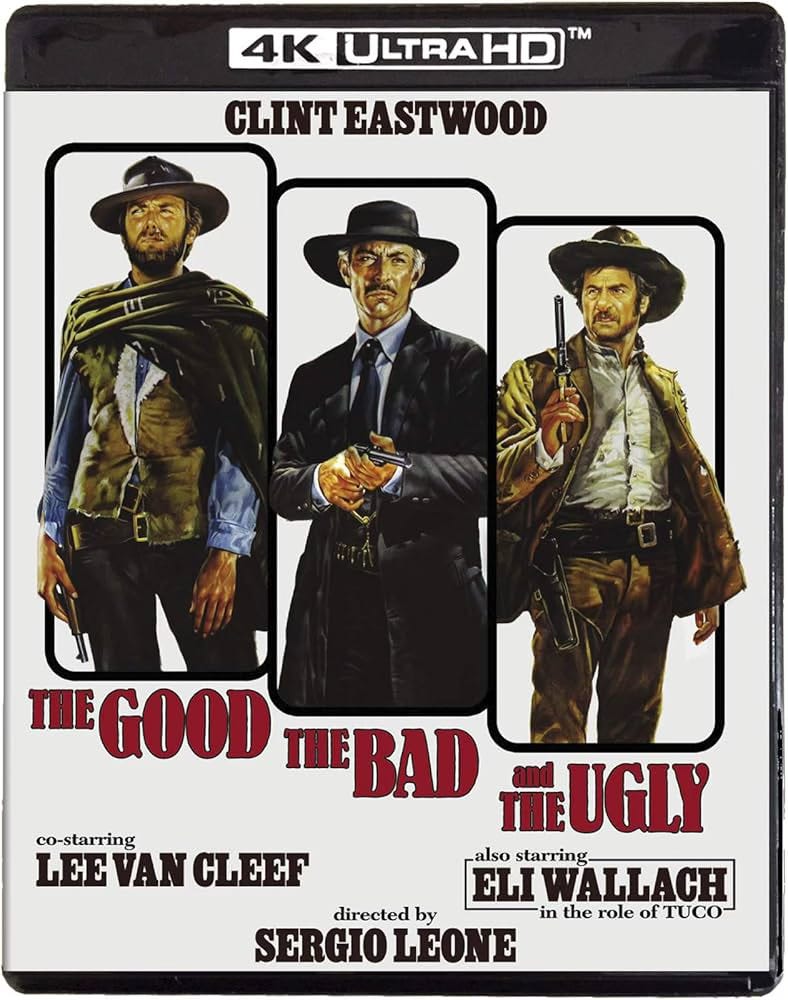

Letters from the Future (of Learning): The Good, The Bad & The Ugly In Trump’s “Ten Principles for Great Schools”

Let’s get something straight: it’s over.

The people have chosen Donald Jessica Trump to be their 47th president, which means he gets to make all the decisions -- including what to do with our nation’s public schools. And leaving aside whether he’ll do away with the U.S. Department of Education altogether, the president-elect has actually been pretty clear about his educational priorities.

Ten of them, to be precise.

So I thought I’d offer a personal review of the Trump plan, via a three-headed ranking system that’s based on the 1966 Clint Eastwood classic (and its triumvirate of protagonists), The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

And away we go.

1. Restoring Parental Rights (UGLY)

I hereby declare “ugly” any principle that is, in fact, little more than a political talking point. And that’s exactly -- and all -- this one is.

To wit: in his explanation of this principle, Trump promises to “turn back the tide of left-wing indoctrination and once again respect the fundamental right of parents to control the education, healthcare, and moral formation of their children.”

OK.

Except to use one hot button issue as an example, all fifty states already allow parents to opt out of vaccines for medical reasons. Thirty states allow parents to opt out for religious reasons. And some allow parents to opt out simply for personal reasons.

Of course, the reason a coordinated push for vaccines exists in the first place is because the Center for Disease Control and Prevention believes it reduces the likelihood that they (and we) get sick. But the point here is that even if you disagree with that premise, you can already opt out.

Similarly, despite Trump’s promise to “support the right of parents to know what their children are being taught in the classroom, to be able to openly communicate any of their concerns with teachers and principals, and to review the budget and spending of their children’s school,” these rights already exist, too.

Public school board meetings, at which budgetary, curricular and spending decisions are shared and reviewed, are required to be open and transparent. Classes have syllabi, teachers have emails and phone numbers, and any parent who wishes to opt their child out of a given book or unit can do so.

“Restoring parent rights,” therefore, is not a meaningful reform principle: it’s a cultural dog whistle.

2. Great Principals and Great Teachers (BAD)

I’m not suggesting this one is BAD because I don’t support great principals and great teachers -- duh -- but because the way the Trump administration proposes we get there is by insisting on “the direct election of school principals by the parents,” and warning that “if any principal is not performing to a high standard, parents should have the right to fire them and select someone who will.”

Can you imagine any other industry entertaining for even a second the idea that a bunch of parents should be the ones to decide who they get to hire and fire? This is the stuff of pitchforks and torches.

But even if we did empower parents this way, what would define the “high standard” to which we are holding them? Because as convenient as standardized reading and math scores may be, it is well established that they alone are not the mark of a great school.

On that point, I’ve had a lot of ideas for a long time now about what a high standard for school performance should be -- here’s a proposal I made back in 2010 -- but I won’t waste my breath here. Because as it stands, Principle Two is just gobbledygook.

3. Knowledge and Skills, Not CRT and Gender Indoctrination (UGLY)

The first time I encountered Critical Race Theory, I was a PhD student at William & Mary. It is dense, scholarly stuff, and although I work in schools all over the country, I have yet to encounter it in any meaningful form anywhere at the K-12 level (and I will bet the farm you haven’t either). So this one gets another UGLY rating, because this is primarily just a talking point.

I say primarily, because the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution does forbid any form of indoctrination in our schools (every public school employee is an agent of the state). As Americans, therefore, we should all oppose political indoctrination in our public schools in any form. But when Trump gets people excited by saying he will “cut federal funding for any school pushing Critical Race Theory, transgender insanity, and other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content on our children,” he is doing little more than organize a witch hunt that is likely to be no more successful than this one.

The gender question is more fraught.

I can understand why for some people, amidst everything else that is rapidly changing in our world, it can feel like a bridge too far to suggest that bathrooms should no longer simply be labeled MALE or FEMALE. A major part of Trump’s appeal is that he offers a return to simpler times. But we can’t deny that although a majority of us do fit into binary labels, some of us, just as clearly, don’t.

The challenge, as always, is finding the best way to expand our notion of what “liberty and justice for all” really means (and requires). It is our most sacred work as Americans — and each generation’s most lasting contribution to the shared task of forming a more perfect union.

4. Love of Country (MOSTLY GOOD)

Which leads us to Principle Four.

As I learned from my former boss and mentor Charles Haynes, America’s greatness stems from our role as the world’s first “new nation:” a place where one’s standing in the civic order is not determined by bloodlines and kinship, but by a shared allegiance to principles and ideals.

So, yes, let’s revitalize our commitment to those principles and ideals. “As America’s history has shown,” Trump writes, “the path to a restored and strengthened unity can be found through the rediscovery of a shared national identity rooted in our Founding.”

But I get nervous when I hear Trump vow to “ensure our children know the truth about the Founding,” or promise to “create a credentialing body to certify teachers who embrace patriotic values and support the American Way of Life.”

Because this is the thing about America’s founding principles: we have never fully embodied them.

Our national story is inspiring and appalling.

And our responsibility is to acknowledge the dialectic of that history -- the heroes and the horrors -- not airbrush it for propagandistic purposes.

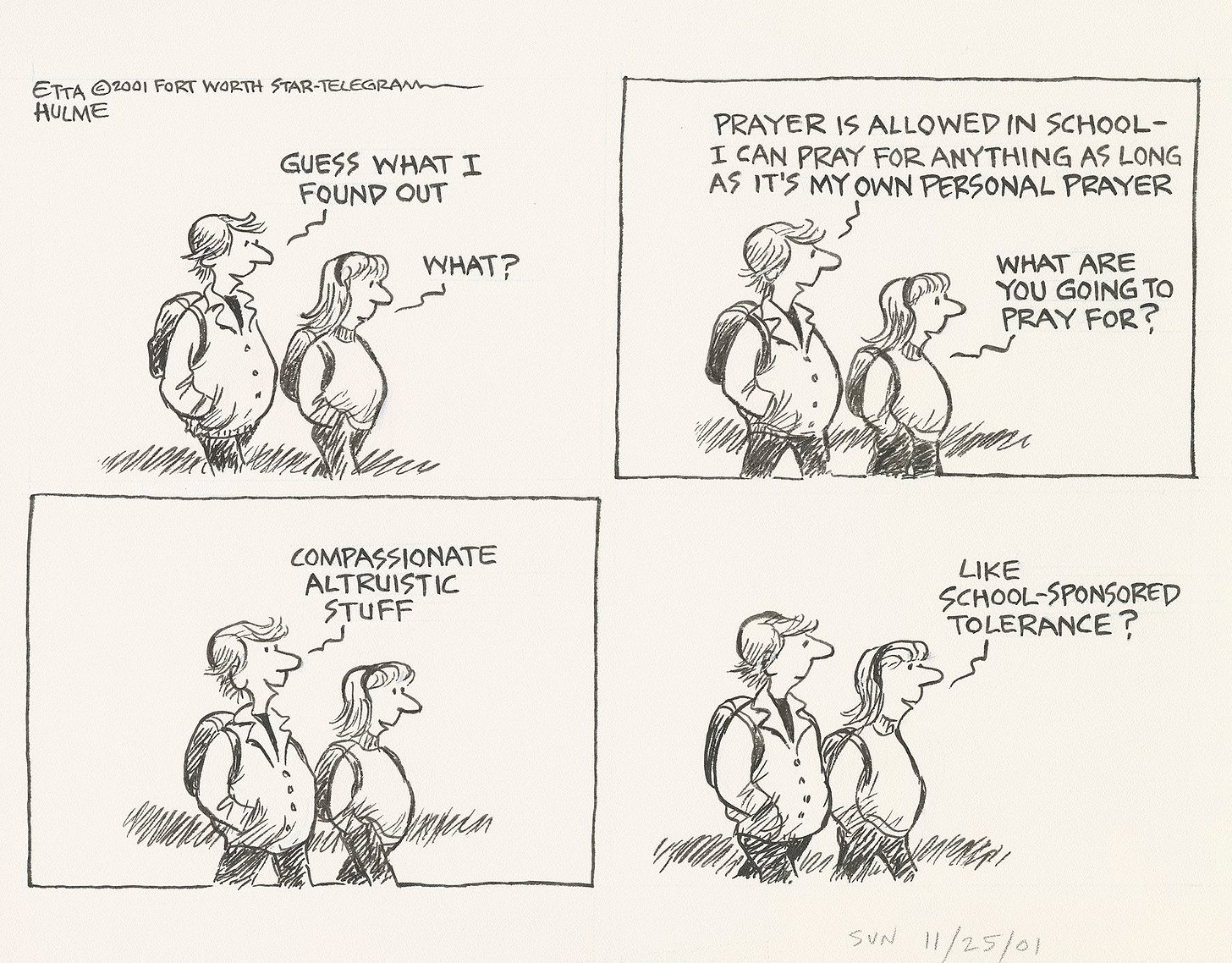

5. Freedom to Pray (BAD)

This is an easy one, thanks once again to the First Amendment, which begins with these sixteen words: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

Therein lie the Constitution's two relevant rulings on religion: the No Establishment Clause (which forbids us from favoring one religion over the rest), and the No Exercise Clause (which requires us to protect each person’s freedom to choose what they believe).

The former applies to our public schools and their employees, which is why school-sponsored prayer is a no-no.

The latter applies to every American student, which protects their right to pray, alone or in groups, and to otherwise express their religious identity.

To help sort fact from fiction, some colleagues and I published a handbook for all of these issues, The First Amendment in Schools. Charles Haynes and Oliver Thomas also published a comprehensive guide to religion and public schools called Finding Common Ground.

But if you don’t want to do all that reading, here’s the headline:

Every American student already has the freedom to pray -- just as every American public school is forbidden from insisting that they do so.

6. Safe, Secure, and Drug-Free (UGLY)

I agree wholeheartedly with the president-elect when he says “greatness in the classroom requires safety in the classroom.” But when Trump promises to “completely overhaul federal standards on school discipline to get violent thugs OUT of the classroom and INTO reform schools and corrections facilities,” this stops being a meaningful proposal and starts being yet another example of the politics of fear masquerading as policy.

And no, arming teachers or hiring armed retirees to patrol our nation’s schools is not a good idea -- see, for example, Uvalde.

Responsible gun legislation, however . . .

7. Universal School Choice (BAD)

This one’s an oldie but a baddie.

In his 2020 State of the Union, then-President Trump renewed a call for tax breaks to provide more scholarships for students to attend private schools. “For decades,” Trump explained, “countless children have been trapped in failing government schools. We believe that every parent should have educational freedom for their children.”

To which I say, buyer beware. And: it’s complicated.

As a resident of Washington, D.C., site of one of the country’s most ambitious school voucher plans to date, and a city in which half of the city’s students attend public charter schools, I support school choice. I helped launch a charter school here. My sons attend another one, and the city is beginning to see some real collaboration between its charter schools and the district. Yet I worry about what could happen if we simply assume the invisible hand of the modern school marketplace – or, worse still, the incentivizing hand of the federal official – will ensure that all children receive equal access to a high-quality public education.

“Markets don’t just allocate goods,” Harvard professor Michael Sandel writes in What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. “They also express and promote certain attitudes towards the goods being exchanged.” And what has occurred over the past thirty years is that without quite realizing it, we have shifted from having a market economy to being a market society.

“The difference is this: A market economy is a tool – a valuable and effective tool – for organizing productive activity. A market society is a way of life in which market values seep into every aspect of human endeavor. It’s a place where social relations are made over in the image of the market.”

In the end, should we define education as a public good, or a private commodity?

Will our efforts to unleash self-interest strengthen or weaken the connective tissue of our civic life?

And will the current trajectory of the school choice movement unleash a virtuous cycle of reforms that improves all schools, or merely add another layer in our historic apartheid system of schooling?

President Trump’s myriad other amoral tendencies notwithstanding, our changing notion of community should be the central concern of anyone who cares about school choice. How can greater choice bring us closer to each other, and to a revitalized notion of civic virtue and egalitarianism (e.g. Principle Four)? And how can school choice reflect this basic truth about democracy – that while it does not require perfect equality, it does require that citizens share in a common life, one that is grounded as much in the “we” as the “me”?

These are the questions we must explicitly ask and answer if we want school choice to become a force for good. But we can’t do that without explicitly debating the extent to which market-based thinking can get us there.

As Professor Sandel reminds us, “when market reasoning is applied to education, it’s less plausible to assume that everyone’s preferences are equally worthwhile. In morally charged arenas such as these, some ways of valuing goods may be higher, more appropriate than others.”

So, yeah. No.

8. Project-Based Learning (GOOD)

Here’s where I get to finally cast a vote for Clint Eastwood. Because president-elect Trump is right when he says that “America’s students are more successful, more engaged, and more prepared for real-world experience when their education involves hands-on projects that aim to approximate what real-world work situations will demand of them.” Consequently, Trump’s promise “to support project-based learning inside the classroom to help train students for fulfilling work outside the classroom” feels like his most consequential principle yet.

(And if you want to learn more, check out Edutopia’s recommended resources on the subject.)

9. Internships and Work Experiences (GOOD)

I’m also a fan of the incoming administration’s intention to “implement funding preferences for schools that actively work to help students secure internships, part-time work, and summer jobs that will set them on the path to long and fulfilling careers.”

This past year alone, I’ve written a number of stories that feature schools and communities that integrate internships and work experiences into the learning day and program: from Cristo Rey in Philadelphia to the citywide effort in Columbus to create a learner-centered ecosystem that prepares young people for the modern workforce.

If the incoming team can further incentivize this practice, good things should follow.

10. Jobs and Career Counseling (GOOD)

Finally, Trump has another winner with his pledge to “implement funding preferences for schools with job and career counselors on-hand.”

As McKinsey reported in its 2021 report on The Future of Work, schools have a lot more to consider these days when it comes to preparing young people for their future (as opposed to our past) -- from constant job switching to higher skills to, yes, the impact of A.I. Consequently, as McKinsey put it, “understanding these macro trends within the global economy is vital to planning for what’s ahead.”

How the Trump administration does these things, of course, is the story of the next four years -- a story that will surely refuse to unfold as neatly as this ten-point-plan suggests.

In the end, no matter how much we wish it to be otherwise, transforming our public schools is not simple and straight-forward.

Nonetheless, the opposition would be wise to take a page from Trump’s playbook by articulating their own set of Principles for Great Schools -- and doing so in a way that feels actionable, accessible, and appropriate for the average American.

I’ll take on that challenge next . . .

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.