Gadfly on the Wall Blog: Teachers Are More Stressed Out Than You Probably Think

When I was just a new teacher, I remember my doctor asking me if I had a high stress job.

]I said that I taught middle school, as if that answered his question. But he took it to mean that I had it easy. After all – as he put it – I just played with children all day.

Now after 16 years in the classroom and a series of chronic medical conditions including heart disease, Crohn’s Disease and a recent battle with shingles though I’m only in my 40s, he knows better.

Teaching is one of the most stressful jobs you can have.

You don’t put your life on the line in the same way the police or a soldier does. You don’t risk having a finger chopped off like someone working in a machine shop. You don’t even have to worry like a truck driver about falling asleep and drifting off the road.

But you do work a ridiculous amount of hours per day. You lose time with family, children and friends. And no matter how hard you work, you’re given next to no resources to get it done with, your autonomy is stripped away, you’re given mountains of unnecessary bureaucratic paperwork, you’re told how to do your job by people who know nothing about education, and you’re scapegoated for all of society’s ills.

Not to mention that you’re expected to buy supplies for your students out of your own pocket, somehow magically raise student test scores but still authentically teach, convince parents not to send their children to the local fly-by-night charter or voucher school and prepare for an unlikely but possible school shooter!

Oh! And the pay isn’t competitive given the years of schooling you need just to qualify to do the work!!

That causes a mighty amount of stress.

One in five teachers (20%) feels tense about their job most or all of the time, according to an analysis by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) in England. In similar professions, only one in eight feel this way (13%).

But those are conservative estimates.

A representative survey of more than 4,000 educators conducted in 2017 by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the Badass Teachers Association (BATs) found even more stark results.

Educators and school staff find their work “always” or “often” stressful 61 percent of the time. Workers in similar professions say that their job is “always” or “often” stressful only 30 percent of the time.

That kind of tension among teachers has consequences. More than half of educators reported that they have less enthusiasm now than at the beginning of their careers.

One respondent commented:

“This job is stressful, overwhelming and hard. I am overworked, underpaid, underappreciated, questioned and blamed for things that are out of my control.”

WORK LOAD

The most obvious cause of teacher stress is the workload.

Though the details vary slightly from study to study, the vast majority highlight this as the number one factor.

The NFER study concluded that teachers work longer hours than people in other professions though a less number of official days. This is because of the school year – classes meet for about 9-10 months but require far more than 40 hours a week to get everything done. In fact, teachers are putting in a full years work or more in those limited days.

For instance, an average American puts in about 260 days at work a year. Teachers average 70 less days but do the same (or more) hours that other employees put in during the full 260 days. But teachers are only paid for 190 days. So they do roughly the same amount of work in a shorter time span and are paid less for it. The result is a poor work-life balance and higher stress levels.

But exactly how many hours do teachers routinely work? It depends on who you ask.

The University College London Institute of Education estimates that one in four teachers works 60 hours a week or more – a figure that has remained consistent for the past 25 years.

According to NFER, teachers work an average of 47 hours a week, with a quarter working 60 hours a week or more and one in 10 working more than 65 hours a week.

Four in 10 teachers said they usually worked in the evenings, and one in 10 work on weekends.

Both of these studies refer to British teachers but estimates are similar for teachers in the United States.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that teachers in both countries are among those who work the most hours annually. The average secondary teacher in England teaches 1,225 hours a year. The average secondary teacher in the United States teaches 1,080 hours a year. Across the OECD, the average for most countries is 709 hours.

Finally, a study focusing just on US teachers by Scholastic, found that educators usually work 53 hours a week. That comes out to 7.5 hours a day in the classroom teaching. In addition, teachers spend 90 minutes before and/or after school mentoring, tutoring, attending staff meetings and collaborating with peers. Plus 95 additional minutes at home grading papers, preparing classroom activities and other job-related tasks.

And teachers who oversee extracurricular clubs put in an additional 11-20 hours a week.

No matter how you slice it, that’s a lot of extra hours.

According to the NFER study, two out of five teachers (41%) are dissatisfied with their amount of leisure time, compared to 32% of people in similar professionals.

This is a prime factor in the exodus of trained professionals leaving the field in droves, sometimes miscalled a teacher “shortage.”

It’s why one in six new teachers leave the profession after just a year in the classroom.

SALARY

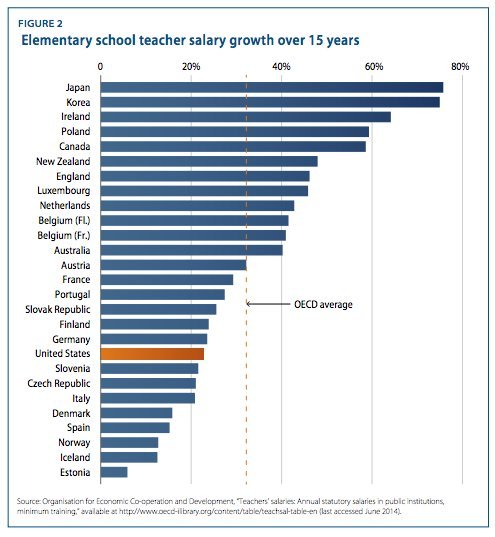

Another contributing factor is salary.

Teacher pay in the United States (and many other countries) is not competitive for the amount of training required and responsibilities put on employees.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, teachers in the United States make 14 percent less than people from professions that require similar levels of education.

Sadly, it only gets worse as time goes on.

Teacher salary starts low, and grows even more slowly.

According to a report by the Center for American Progress, on average teachers with 10 years experience only get a roughly $800 raise per year. No wonder more than 16 percent of teachers have a second or third job outside of the school system. They simply can’t survive on the salary.

They can’t buy a home or even rent an apartment in most metropolitan areas. They can’t afford to marry, raise children, or eke out a middle class existence.

BACK TO WORKLOAD

So if we wanted our kids to have the same quality of service children received in this country only a decade ago, we’d need to hire almost 400,000 more teachers!

That’s how you cut class size down from the 20, 30, even 40 students packed into a room that you can routinely find in some districts today.

The fact that we refuse to invest in our schools only increases the workload of the teachers who are still there. They look around and see students in desperate need and have to choose between what’s good for them, personally, and what’s good for their students.

THAT’S why teachers are working so many unpaid hours. They’re giving all they have to help their students despite a society that refuses to provide the necessary time and resources.

And make no mistake, one of those resources is having enough teachers to get the job done.

RESPECT

For a lot of teachers, the issue boils down to respect – lack of it.

The fact is teachers are extremely important – the most important in-school factor for student success.

However, that doesn’t make them the most important factor in the entire learning process.

Roughly 60% of academic achievement can be explained by family background – things like income and poverty level. School factors only account for 20% – and of that, teachers account for 15%. (see Hanushek et al. 1998; Rockoff 2003; Goldhaber et al. 1999; Rowan et al. 2002; Nye et al. 2004).

Estimates vary somewhat from study to study, but the basic structure holds. The vast majority of impact on learning comes from the home and out-of-school factors. Teachers are a small part of the picture. They are the largest single factor in the school building, but the school, itself, is only one of many components.

The people who know teachers the best—parents, co-workers and students—show much more respect for teachers than elected officials and media pundits, many of whom rarely set foot in a classroom, according to the 2017 BATs and AFT Quality of Work Life Survey.

While educators feel most respected by their colleagues, they also indicated that their direct supervisors showed them much more respect than their school boards, the media, elected officials and U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. A total of 86 percent of respondents did not feel respected by DeVos.

Most educators said they felt like they had moderate to high control over basic decisions within their own classrooms, but their level of influence and control dropped significantly on policy decisions that directly impact their classroom – such as setting discipline policy, performance standards and deciding how resources are spent.

“This lack of voice over important instructional decisions is a tangible example of the limited respect policymakers have for educators,” the report concluded.

Sometimes this lack of respect leads to outright bullying.

A total of 43 percent of respondents in the public survey group reported having been bullied, harassed or threatened at work in the last year. Of these reports, 35% included claims of having been bullied by administrators, principals or supervisors, 23% by co-workers, 50% by students, 31% by students’ parents. Many claimed to have been bullied by multiple sources.

This is a much higher rate of bullying, harassment and threats than workers in the general population.

I, myself, have experienced this even to the point of being physically injured by students multiple times – nothing so serious that it put me in the hospital, but enough to require a doctor’s visit.

And to make matters worse, one-third of respondents said that teachers and faculty at their schools did not felt safe bringing up problems and addressing issues.

CONCLUSIONS

Teacher stress is a real problem in our schools.

If we want to provide our children with a world class education, we need to look out for the educators who do the actual work.

We need to drastically reduce the workload expected of them. We need to hire more teachers so the burden can be more adequately sustained. We need to increase teacher salary to retain those already on the job and to attract the most qualified applicants in the future. We need to stop blaming teachers for every problem in society and give them the respect and autonomy they deserve for having volunteered to do one of the most important jobs in any society. And we have to stop bullying and harassing them.

As a nation, our children are our most valuable resource. If we want to do what’s best for the generations to come, we need to stop stressing out those brave people who step up to guide our kids into a brighter tomorrow.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.