Radical Scholarship: VAM Fails Test, Again: The Bizarro World of Education Reform

The great state of South Carolina (and for full effect, you should hear that with “great” and “state” rhyming, sort of, with “pet” because that is how the good ol’ boy patriarchy says it around here) continues down a path all too familiar across the U.S.: adopt any and all education reform policies that other states are rushing to implement, even (and maybe especially) when research fails to support the practices.

I have catalogued the inexcusable political and public support in SC for retaining third graders based on high-stakes testing scores—a policy directly linked to Read, Florida.

And despite equally ample evidence to the contrary about basing teacher evaluations on value added methods (VAM), also a corrosive policy in Florida, Charleston, SC is moving forward with BRIDGE, characterized by Peter Smyth as A BRIDGE to I Have No Clue Where.

Public policy implementing grade retention, VAM, and lingering commitments to merit pay—just to name a few—continues to thrive in SC and across the U.S., seemingly as a bold-faced snub of the idealistic (and increasingly Orwellian) call in No Child Left Behind that education policy must be “scientifically based.”

Education Reform in Bizarro World

In the DC Universe, Superman has often encountered Bizarro World, Htrae. Education reform is no less bizarre with the political and public mania for policies that have been and continue to be refuted by large bodies of research.

For example, Edward H. Haertel’s Reliability and validity of inferences about teachers based on student test scores (ETS, 2013) now offers yet another analysis that details how VAM fails, again, as a credible policy initiative—with a few caveats*.

Briefly, the analysis by Haertel offers the following:

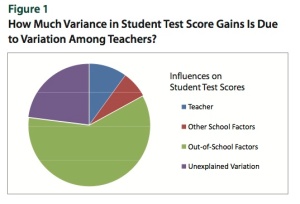

- First, Haertel addresses the popular and misguided perception that teacher quality is a primary influence on measurable student outcomes. As many researchers have detailed, teachers account for about 10% of student test scores, as shown in this graphic (see p. 5):

- Next, Haertel confronts the myth of the top quintile teachers (pp. 6-7*), outlining three reasons that arguments about those so-called “top” teachers’ impact are exaggerated.

- Haertel also acknowledges the inherent problems with test scores and what VAM advocates claim they measure—specifically that standardized tests create a “bias against those teachers working with the lowest- performing or the highest performing classes” (p. 8).

- The next two sections detail the logic behind VAM as well as the statistical assumptions in which VAM is grounded (pp. 9-13), laying the basis for Haertel’s main assertion about using VAM in high-stakes teacher evaluations.

- The main section of the report, An Interpretive argument for value-added model (VAM) teacher effectiveness estimates (pp. 14-25), reaches a powerful conclusion that matches the current body of research on VAM:

These 5 conditions would be tough to meet, but regardless of the challenge, if teacher value-added scores cannot be shown to be valid for a given purpose, then they should not be used for that purpose.

So, in conclusion, VAMs may have a modest place in teacher evaluation systems, but only as an adjunct to other information, used in a context where teachers and principals have genuine autonomy in their decisions about using and interpreting teacher effectiveness estimates in local contexts. (p. 25)

- In the last brief section, Haertel outline a short call for teacher evaluations grounded in three evidence-based “common features”:

First, they attend to what teachers actually do — someone with training looks directly at classroom practice or at records of classroom practice such as teaching portfolios. Second, they are grounded in the substantial research literature, refined over decades of research, that specifies effective teach- ing practices….Third, because sound teacher evaluation systems examine what teachers actually do in the light of best practices, they provide constructive feedback to enable improvement. (p. 26)

Haertel’s concession that VAM has a “modest” place in teacher evaluation is no ringing endorsement, but it certainly refutes the primary—and expensive—role that VAM is playing in the rush to reform teacher evaluation in SC and across the U.S.

In the irony of ironies that can occur only in the Bizzaro World of education reform, each time VAM is tested, it fails, and each time it fails, more states line up to implement it.

* Haertel offers a more than generous analysis of the Chetty, Friedman, and Rockoff (2011) claim that teacher impact can be extrapolated into adult earning for students. I urge readers to examine Bruce Baker‘s and Matthew Di Carlo‘s more nuanced and cautious analyses of those claims.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.