The Art of Teaching Science: Who Benefits When Student PISA Scores Decline?

What’s bad for you might be good for others. In fact, in the world of international tests, American student’s scoring low on the recent PISA test is actually very good for business, profiteers, think tanks, and those who think America’s schools are failing. Using average scores, the US was ranked 30 in maths, 20 in reading, and 23 in science, a downward trend that plays into the hands of the “doom and gloom” education naysayers. In this post I want to argue that using PISA tests to evaluate a nation’s educational system is not only unscientific, but the conclusions that are reached and “solutions” proposed lack the wisdom needed to support teaching and learning.

Zooming In on the PISA Data

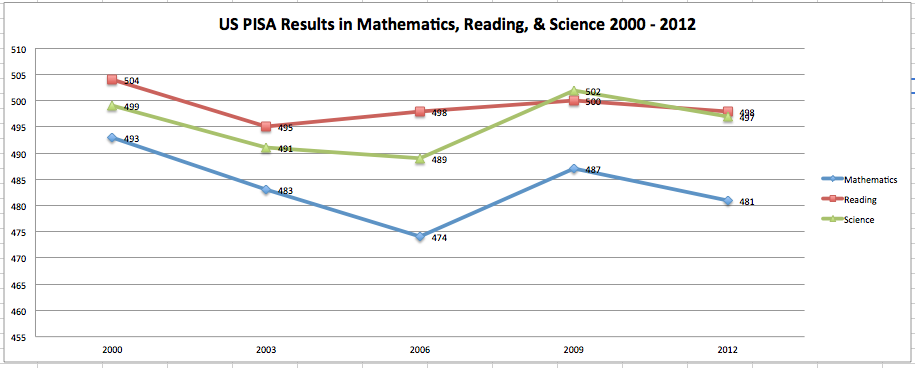

If you look at Figure 1, it seems that student test scores are in decline from 2009 to 2012. In math student scores plunged 6 points, a 1.2% drop in the average score of American students. In reading, the scores dropped 0.4%, and in science scores slumped 0.9% from 2009 to 2012. To leaders at Achieve, a company that stands to benefit from “failing schools” based on such plummeting scores. The PISA results are just the ticket to further their claim that American schools need to be fixed, and they are ready to do the job. Achieve wrote the Common Core, and the Next Generation Science Standards. Between the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Race to the Top, millions of dollars are being pumped into the implementation of the these two sets of standards. When these three entities look at Figure 1, they interpret the results using an ideological framework based on an authoritarian standards-based and data driven model. Although the U.S. has had standards in place in all the states during the period shown in the graph, Achieve, Gates, and Duncan (AGD) claim that an important step to fix the American school problem is the adoption of the Common Core.

The Brown Center Report on American Education (2012) showed that standards (whether they were good or bad) have had no affect on changing student achievement scores measured by NAEP, which many researchers consider a much more powerful measure of student learning in American classrooms. Author Tom Loveless explains that neither the quality nor the rigor of state standards was not correlated with NAEP scores. Loveless suggests that if there was an effect, we would have seen it since all states had standards in place since 2003.

Yet AGD would have us believe that implementing a new set of standards in American schools will cause momentous change in student achievement.

Figure 1. PISA Scores for American 15 year-olds, 2000 – 2012

Zooming Out

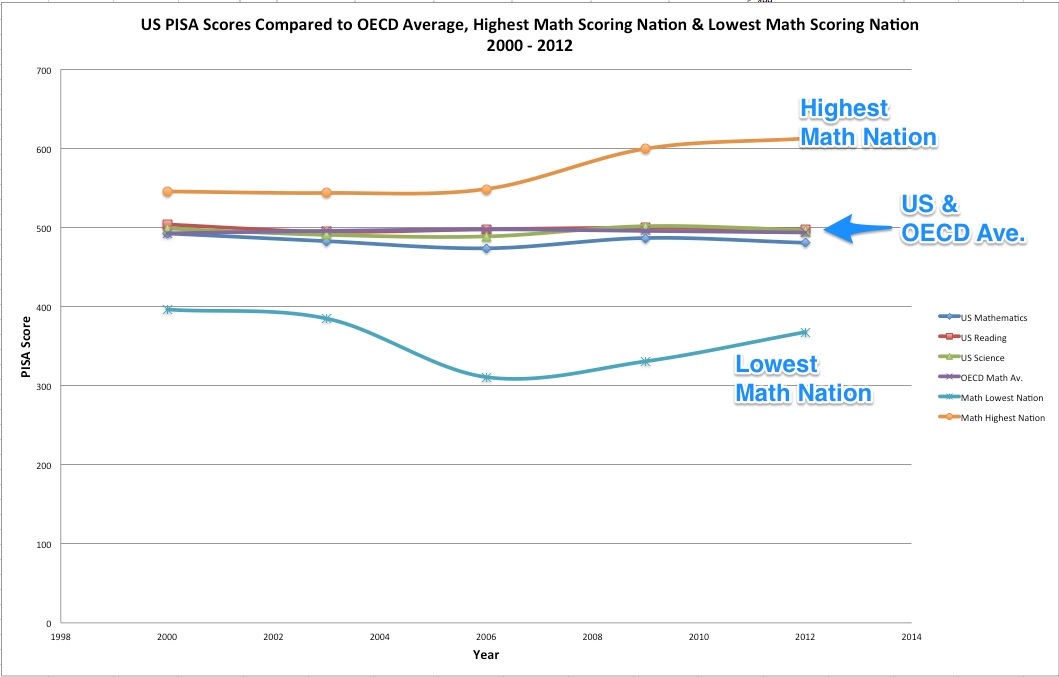

What happens if we zoom out and look at the data from a different perspective. Figure 2 compares US PISA scores in math, reading and science with the OECD average for all nations that participated in the PISA tests from 2000 – 2012. In this case, I used a scale that would also include the scores of highest and lowest scoring nation for the years that PISA was administered. When you look at American scores over the past dozen years, they seem as a flat line in the same place as the average scores posted by all nations. In fact it is difficult to distinguish one score from another.

The naysayers look at this data and claim that the sky is falling, and that if we don’t fix American education, our students will not be able to compete with students from the “highest scoring” nations. Not only that, if this trend continues, it will affect the nation’s economy. Both of these conclusions are simply not supported in the research literature. They are nothing more than political and authoritarian ideology.

American student scores on international tests are predictable and sustainable. But, because the reformers such as Achieve, Gates and Duncan use a market and business strategy that compels schools to increase student achievement EVERY year, and if teachers don’t fulfill this ridiculous goal, their jobs will be jeopardized. Schools risk being closed, or taken over by private charter corporations. If you don’t believe me, please read any one of my posts on Georgia’s Race to the Top to discover how the money is spent, how the state has developed questionable relationship with charter companies, Teach for America and the New Teacher Project.

The graph in Figure 2 actually shows how stable is American education. But the doom and gloom naysayers use the graph to warn Americans that we are losing the global competition war, much like the Cold War. In fact, much of the reasoning used today to claim American education is “behind” other advanced nations is very similar to the claims made during the Sputnik Era, the Cold War and the Race for Space. During that period, according to scientists, our education system was antiquated, and lacked the rigor needed for Americans to understand science, mathematics and technology. (For a full discussion of this, please see Scientists in the Classroom by John L. Rudolph (Library Copy). When the “nation was at risk,” during the 1980s, it was the economies of Germany and Japan that posed a threat to America. The threat today is from those nations that score high on international tests, such as PISA.

These tests do not measure what many in America consider important goals of education, including creativity, social skills of communications and collaboration, interdependence, and being innovative. In her newest book, Nel Noddings questions those who consider that American schools are failing. She reminds us that comparing scores from different nations does not take into account differences in these countries. In fact, if we do compare countries that are alike, we find that their scores are similar. She suggests that we should not obsess over international scores. She says:

We are now in the 21st century, and it is time to reduce the emphasis on competition. Cooperation will be a major theme throughout this book. We are living in a global community— that is, we are trying to build such a community— and the keywords now are collaboration, dialogue, interdependence, and creativity. This does not mean that there should be no more competition; some competition is both necessary and healthy, and it often promotes better products and performances. But in the 21st-century world, collaboration is the new watchword. People must work together to preserve the Earth and to promote the welfare of all its inhabitants. Noddings, Nel (2013-01-25). Education and Democracy in the 21st Century (pp. 1-2). Teachers College Press. Kindle Edition. (Library Copy)

International test scores do not measure interdependence and social skills, nor do they measure innovation. They measure factual knowledge. PISA claims to measure students’ ability to apply knowledge, yet the test questions are not localized, and remain outside any kind of context that would be meaningful to students. Relying on international test scores to measure a nation’s academic abilities is a dead-end.

In Diane Ravitch’s book (Library Copy), The Reign of Error, she references research done by Keith Baker, a former researcher for the U.S. Department of Education. In his research, he raised question including “Are international tests worth anything? Do they predict the future of a nation’s economy? Ravitch reports that Baker reviewed data going back to 1964 to answer these questions. Ravitch reported on his research and this is what she said:

Baker looked at per capita gross domestic product of the nations whose students competed in 1964. He found that “the higher a nation’s test score 40 years ago, the worse its economic performance on this measure of national wealth— the opposite of what the Chicken Littles raising the alarm over the poor test scores of U.S. children claimed would happen.” The rate of economic growth improved, he held, as test scores dropped. There was no relationship between a nation’s productivity and its test scores. Nor did high test scores bear any relationship to quality of life or livability, and the lower-scoring nations in the assessment were more successful at achieving democracy than those with higher scores. Ravitch, Diane (2013-09-17). Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools (Kindle Locations 1500-1505). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

We’re Number 1

There is an incessant want in this country to be number 1, and in education, international tests such as PISA, and TIMSS give the arena for the competitions to take place. Unfortunately, using student test scores to set up league tables listing the “highest performing” nations in decreasing order toward the “lowest performing” nations creates an aura of competition that is unfortunate to our wish to help students learn. Nel Noddings provides a powerful summary of this idea. She says:

Recently, President Obama advised— to considerable applause— that we (the United States) must out-innovate, out-educate, and out-build the rest of the world. This is an example of 20th-century thinking that many of us believe must be put behind us. From one perspective, we are urged to reclaim the ways that, in the 20th century, made us great. From a second perspective, those ways are thought to be dangerous. Habits of domination, insistence on being “number one,” evangelical zeal to convert the world to our form of democracy, all belong to the days of empire. In the 21st century, without deriding the accomplishments of the 20th century, we must vow not to repeat the horrors of war that accompanied our rise to world power; it is time to recover from the harm done by such thinking and look ahead to an age of cooperation, communication (genuine dialogue), and critical open-mindedness. Noddings, Nel (2013-01-25). Education and Democracy in the 21st Century (p. 2). Teachers College Press. Kindle Edition.

What is your interpretation of the PISA data as shown in the graphs in Figures 1 and 2?

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.