Teachers College Press: How Charter Schools Control Access and Shape Enrollment

What does “public” mean for a “public charter school”? The state charter school statutes that allow charter schools to exist invariably designate them as public schools. Major advocacy organizations like the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools trumpet the school’s public status. But the truth is that some charter schools are a lot less public than others.

A few weeks ago, you may have read a newspaper article about charter schools in New Mexico, where state law requires charter schools to accept all applicants for available seats. If more students apply than there are seats available, the law requires charters to use a lottery—albeit after priority is given to the children of the school’s employees and to siblings of already-enrolled students.

Importantly, the state law also addresses access at the pre-lottery stage, where it prohibits charters from asking applicants for more than “minimal” information. This provision is intended to keep the charter schools from biasing their pool of potential lottery winners by discouraging applicants they might consider less desirable. A lottery is only as fair as its entry requirements.

According to the article in the Santa Fe New Mexican, a law firm called Pegasus Legal Services reviewed a sampling of charter school applications and found that some went beyond asking for minimal information. In particular, the schools requested information about the applicant students’ special-education needs.

When called out, some charter school administrators quickly brought their applications into compliance. But others insisted that the information was important to seek—precisely because of its potential to screen those less desirable applicants. The newspaper article quotes the director of a charter school called the Albuquerque Institute for Math and Sciences at the University of New Mexico, who explained that her school might not be a good fit for some students with special needs. She also noted that the school’s application is attached to a contract that the family must sign, the preface of which reads, “AIMS@UNM is a school of choice and is not appropriate for every student.” The contract explains that all applicants must, in order to attend, have the requisite “intellectual ability.”

Our research for School’s Choice: How Charter Schools Control Access and Shape Enrollment taught us that such philosophies about limiting access are not uncommon among charter school administrators. In fact, we discovered that the charter school system has in place a variety of incentives and disincentives that actually penalize charter schools if they pursue broad public access. By contrast, charter school administrators inclined to limit public access find their schools rewarded with more prepared students who are less expensive to educate and who generate plaudits from politicians and media looking for feel-good stories about schools with unusually high test scores. In states like Arizona, these selective charter schools are even rewarded with extra funding.

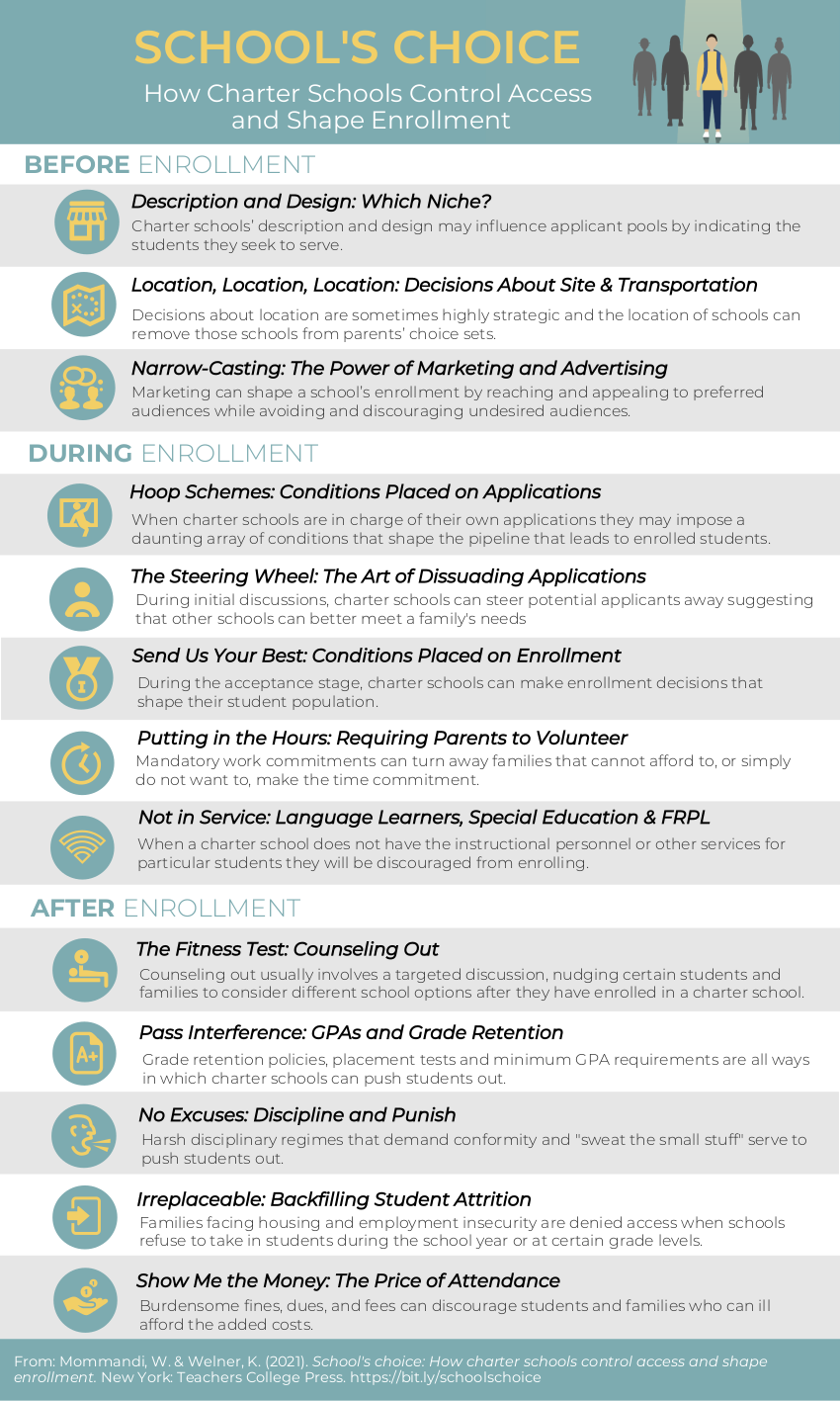

We grouped our findings into 13 broad categories containing the many different ways that charter schools shape their enrollment. The above-described practice in New Mexico is included in a category we titled, “Hoop Schemes: Conditions Placed on Applications.” But we found that students with special needs are also harmed by several other types of practices, including: school design and marketing that signals that these students are unwelcome; steering away parents during enrollment, in part by explaining that the school has few resources or services that meet the needs of special-education students; counseling out enrolled special-needs students or telling them that if they remain they will be retained in grade; and of course, extreme and burdensome discipline.

As shown in the infographic below, these practices sometimes occur pre-enrollment, sometimes during the enrollment process, and sometimes after students are enrolled. The effects are cumulative, with the result that charter school enrollment is often very unrepresentative of the larger public. Some charter schools have taken affirmative steps to welcome and serve all students, but until the incentives change they will be swimming upstream.

State and federal laws addressing areas such as school finance, school accountability, transportation and authorization can help change the perverse incentives and rules driving problematic practices. This would make charter schools more public. In a school-choice context, it would create a more idealized neoliberal vision of a system of public schools giving access to all parents who are interested and able to find the best option for their children.

At the end of the day, however, we propose a different ideal. In a truly public school system, no child’s access to learning opportunities should be allocated pursuant to a parent’s efficacy in working the system or the system’s ability to influence parents. That is, a public school system should not stratify quality, opportunity or access. Whether due to a parent’s choice or a school’s choice, no child’s choices in life should be rationed.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.