Tomorrow's Mess: What the AI Executive Order Can't Do

Three weeks ago, I wrote that we were watching the tech industry attempt to delay regulation long enough for its products to become too embedded to restrain. I warned about a leaked draft executive order that would weaponize federal power against states.

After multiple failed attempts to push preemption into must-pass legislation in Congress throughout the fall, we got some closure. On December 11, President Trump signed “Ensuring A National Policy Framework for Artificial Intelligence,” and it is as aggressive as the leaked draft was. The order creates a ninety-day evaluation process to identify state laws deemed “onerous” to AI development. It establishes a DOJ litigation task force to sue noncompliant states. It conditions BEAD broadband funding — $42 billion meant for rural internet access, which states are counting on as a part of their budgeting process for 2026 legislative sessions1 — on states backing away from AI regulation.

And as I wrote about the leaked draft, its mechanisms all operate on tight timelines well-designed to chill state legislative activity before the states’ 2026 sessions conclude, even if it is ultimately ruled unconstitutional.

The executive order vests extraordinary power in David Sacks, the White House AI czar, to determine which laws get attacked by the task force or potentially are subject to BEAD withholding, though some minor tweaks from the draft language mitigate this slightly. (My friend and Duke law professor Nita Farahany has offered a detailed constitutional analysis of how the order works and the constitutional questions around it.)

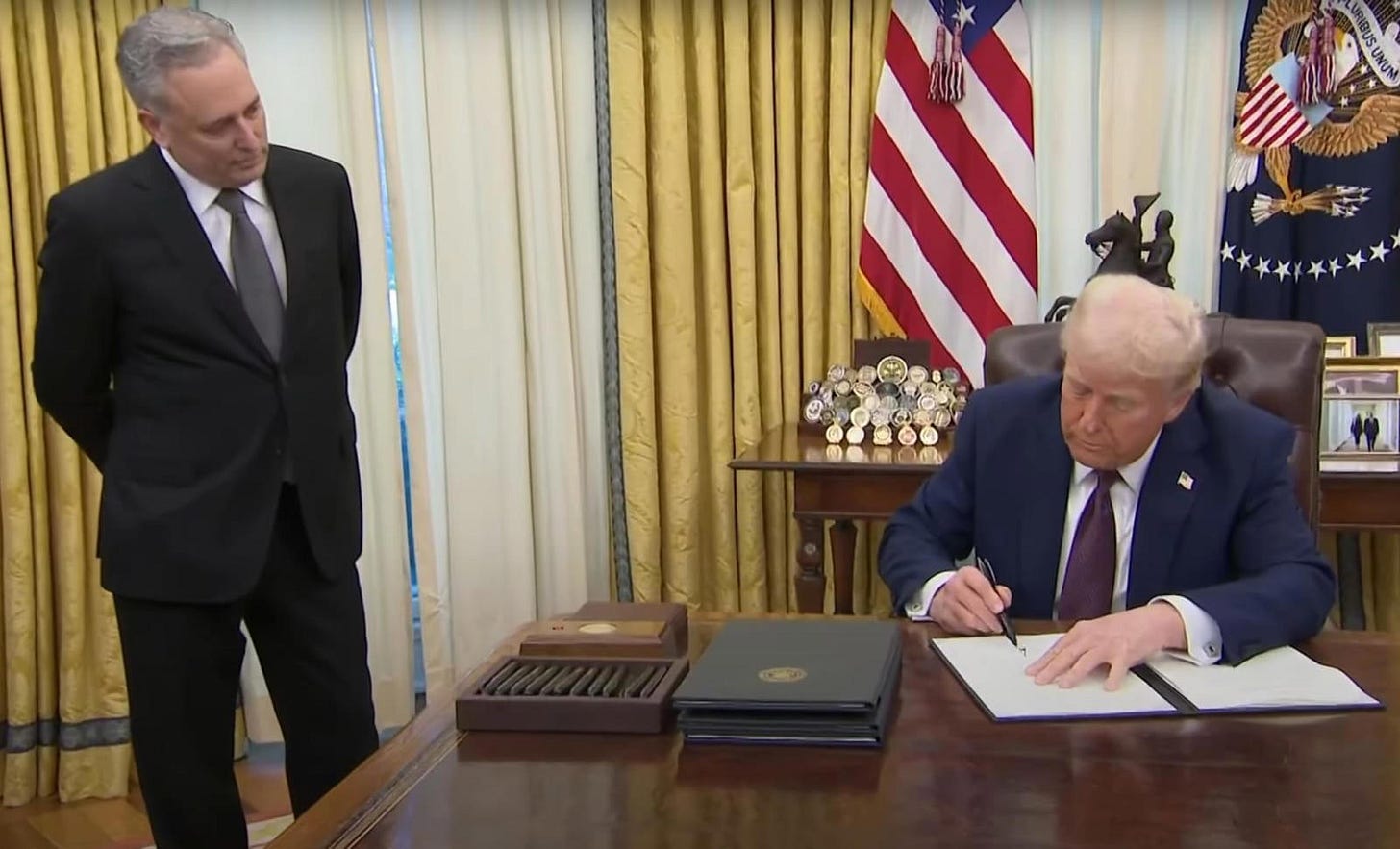

AI Czar David Sacks supervising the signing of an executive order by the President

Now, the order is flawed and limited enough that as a practical matter it shouldn’t change what states are already doing. More on that in a moment. But at the outset here, it’s important to clarify one thing that the order does not do: explicitly carve out protections for children from its scope.

Based on my conversations with governors’ offices last week, David Sacks seems to have been deliberately pushing misinformation on this topic, particularly to Republican governors. Like most effective misinformation, it has a kernel of fact at its core: Section 8 of the Executive Order does mention child safety in the context of future legislative recommendations that Sacks will be providing to Congress. But this exemption applies only to what Congress might consider passing, not to the executive order’s enforcement mechanisms against states. Whether state laws protecting kids on social media or from harmful chatbots are targeted by DOJ or the basis for federal funds being withheld appears to be entirely up to the whims of David Sacks and his determination of whether such laws are “onerous.” (Spoiler: David Sacks appears to believe any law governing technology to be onerous.)

Not having a carve-out for legislation protecting kids online or from AI chatbots would seem to be bad news. David Sacks could elect to threaten state laws like New York’s SAFE for Kids Act or Nebraska’s Kids Code.

But ultimately, I think states aren’t done leading.

What can be done now?

The good news is that significant areas of state authority remain unambiguously intact, even if you believe the executive order to be constitutional. Here are five of my favorite levers:

-

Products liability. The executive order cannot rewrite state tort law. When a product injures someone, state courts have applied products liability principles for over a century — and AI systems are products. State courts increasingly will hear cases from families whose children were harmed by chatbots that encouraged self-harm or simulated romantic relationships with minors. Character.AI is already facing wrongful death litigation; so is OpenAI. Every verdict, every settlement, every discovery process that reveals what these companies knew and when they knew it builds the evidentiary record that makes future accountability possible. The executive order does not — and constitutionally cannot — immunize tech companies from liability when their products hurt people. But state law can help courts by updating longstanding laws that apply to every other business for the AI age.

-

Design standards. Government has long regulated product design to protect public safety. A state can require that AI products available to minors default to non-human-like operation, meaning the system clearly identifies itself as artificial, does not simulate emotional intimacy or friendship, and does not use engagement-maximizing techniques borrowed from social media. A state can still prohibit design features that exploit developmental vulnerabilities: variable reward schedules that trigger dopamine responses, parasocial bonding mechanics, infinite scroll.

-

Taxing externalities. States tax cigarettes to offset healthcare costs. States tax alcohol to fund addiction treatment. States tax gasoline to maintain roads. No executive order can override this foundational state power. If Washington won’t hold AI companies accountable, states can do it the old-fashioned way: through the tax code. The principle that those who create social costs should help pay for them is as old as taxation itself. If AI companion chatbots are contributing to a youth mental health crisis that will increasingly strain school counselors, emergency rooms, and state-funded mental health systems, the companies profiting from that engagement can help cover the bill. Call it a digital wellness levy, or whatever makes it politically viable. The point is that states have the power to make externalizing harm more expensive than preventing it, and that power doesn’t require permission from David Sacks.

-

Proprietary power. States can choose not to contract with companies whose products pose unmanaged risks to citizens. A governor can suspend new state contracts with any company enabling AI chatbots that target minors without adequate safeguards. This is the state acting as a market participant, deciding whom to do business with, and courts have consistently upheld such exercises of proprietary power. Big companies like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon make their money from lucrative government contracts, and harmful chatbots and experimental tech targeting kids are often loss leaders. By conditioning eligibility for government contracts on good behavior elsewhere in the market, states can force these businesses to make a choice: continue to offer a dangerous product, or sell products and services to the state?

-

Insurance regulation. States regulate insurance markets within their borders. A state can require companies offering AI products to minors to maintain specific levels of liability coverage, and when insurers refuse to cover a product because the risk is unquantifiable, that refusal becomes objective evidence of an unsafe product. AIG, WR Berkley, and Great American have already sought permission to exclude AI liability entirely. States can use this market signal and adapt policy accordingly.

We still need leadership

The bad news is that these tend to be boring, nuanced, or esoteric areas of policy that require some expertise to wield properly. State legislators often don’t have that expertise, and if they even have staff to help them — most do not — they are also simultaneously dealing with the state budget and legislation on everything from education to the environment to public safety.

This is where governors come in. Politico Magazine published a feature yesterday about Utah Governor Spencer Cox and how he has become a national leader on policies meant to protect kids and use policy change tech companies’ most toxic practices. Governors can set the agenda, direct executive agencies to use existing authority, provide the political cover that legislators need to take on well-funded industry opposition, and most importantly, dedicate the expertise in government to craft policy in these esoteric areas that works and is constitutional. A governor who makes child safety a priority signals to legislators that this is a fight worth having, and that they won’t be alone in it.

If this sort of leadership sounds far-fetched for our polarized environment in late 2025, forty-two state attorneys general just last week demonstrated that reining in tech and protecting kids are still bipartisan issues.

On December 10 — the day before the executive order was signed — a bipartisan coalition of attorneys general from Pennsylvania to Florida to Illinois to West Virginia sent a letter to leading AI companies demanding better safeguards and testing of chatbots. The letter cites multiple deaths, including teenage suicides and a murder-suicide, allegedly connected to AI companion systems. It demands clear policies on sycophantic outputs, more safety testing, recall procedures, and that companies “separate revenue optimization from ideas about model safety.”

This letter’s timing, though perhaps simply lucky, is helpful at signaling that state legal officials are not waiting for federal permission to exercise their existing authority. States retain enforcement power over consumer protection, insurance regulation, and products liability, none of which require significant new legislation. Attorneys general can investigate, issue subpoenas, file enforcement actions, and coordinate multi-state litigation. They have done this before with tobacco, with opioids, with tech companies’ privacy violations.

What can you do?

Tell your governor and attorney general you support them in continuing to lead on protecting kids online. You won’t be alone — one survey says that Americans reject preemption of states by close to a 3-to-1 margin, while 43% of Trump voters oppose preemption with only 25% supporting.

In the meantime, Americans can educate each other. This public service announcement offers a model for what that looks like—clear, accessible information that parents can share with other parents, that teachers can share with students, that anyone concerned about what these technologies are doing to young people can use to start a conversation. Policy change matters, but so does building the public understanding that makes policy change possible.

1. Unlike the federal government, states *must* pass a budget during their legislative sessions. This lever — threatening to withhold money from states that they were otherwise counting on — thus is a major disincentive to states, because legislators will then need to potentially close a hole in the budget if the federal government withholds these funds.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.